by admincat | Apr 4, 2022 | Art & Stress Relief, Art Consultant

Remote learning is necessary, but there are many challenges

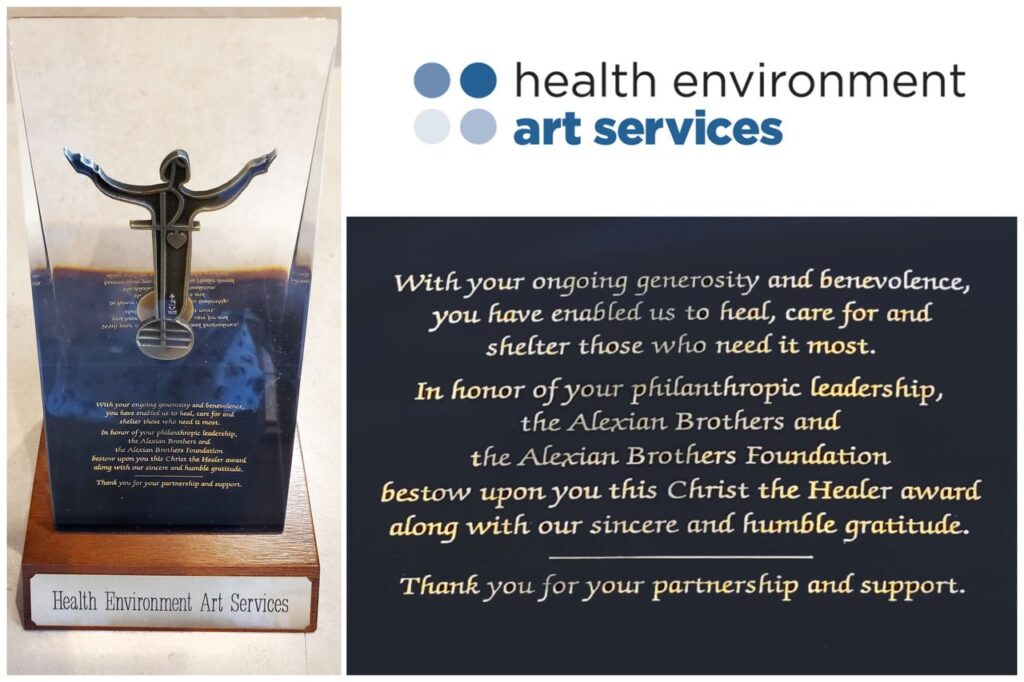

When it became clear that DePaul’s Theatre School would no longer be able to hold classes in person after the novel coronavirus, Chair of Theatre Studies Coya Paz held a meeting with students. In part, she and other faculty members were looking for suggestions on how to accomplish the unprecedented: moving an inherently communal, visceral medium online. Since then, the ideas have flowed fast and loose: radio plays, an increase in playwriting courses, even a class that incorporates Dungeons & Dragons. If you asked Paz last week, she would have said that theater was a fundamentally live art. But because that answer has changed by necessity, the questions change, too.

When it became clear that DePaul’s Theatre School would no longer be able to hold classes in person after the novel coronavirus, Chair of Theatre Studies Coya Paz held a meeting with students. In part, she and other faculty members were looking for suggestions on how to accomplish the unprecedented: moving an inherently communal, visceral medium online. Since then, the ideas have flowed fast and loose: radio plays, an increase in playwriting courses, even a class that incorporates Dungeons & Dragons. If you asked Paz last week, she would have said that theater was a fundamentally live art. But because that answer has changed by necessity, the questions change, too.

“It goes back to this question of, either we think our work matters or it doesn’t. And if we think it matters, it matters now as much as it did last week,” Paz said.

On paper, Paz’s predicament is far from unique — across the country and across Chicago, colleges and universities are shutting down in response to the spread of coronavirus, moving instruction online via platforms like Zoom. But students studying the art of any kind — visual or performing — are met with particular challenges, whether that means losing the opportunity to stage a play, use studio space and materials, or collaborate with their peers. Though the image of students dancing in front of a webcam is a funny one, the reality is, for the most part, anything but. Izzy Schroeder, a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago who works with ceramics, was left with limited options as she saw them: take home 200 pounds of clay, or wait out the storm without materials.

“I’ve talked to some of my friends at other schools and I understand that they’re losing opportunities and experiential learning as well,” Schroeder said. “But it definitely hit us hard, because we had to take the time to figure out if we wanted to do something outside of the studio, how we could do that? And I think a lot of us came to the realization that we can’t.”

SAIC student Kay Liu agreed: beyond access to technology and materials, art students often depend on in-person interactions with professors throughout projects, as well as in-person critiques. And though MFA student Anna Christine Sands is able to meet with her advisor virtually, those meetings involve sharing a screen as opposed to sharing tangible work — and nothing can substitute for a creative environment, working side-by-side with other artists.

Though the technology for online classes has been tried and tested in recent years, formatting isn’t necessarily a boon for the arts. Often, according to the University of Chicago doctoral candidate Ailsa Lipscombe, who studies Music History and Theory, online platforms include functions that normally help to mimic a classroom environment — automatically putting other students on mute when one is speaking, for instance — but actually detract from ensemble students’ typical learning, which relies on simultaneous sound. While UChicago’s music department is working to mitigate challenges, collecting free software licensing and renting instruments, Director of Undergraduate Studies Jennifer Iverson noted that the real challenge is adaptability, keeping education accessible while moving students forward on both academic and creative paths.

“We can’t expect that online courses are a replacement or a seamless substitute for what we would’ve had in person,” Iverson said. “But nothing about our lives in this moment is comparable to the normal.”

And some students have broader concerns. Samantha Weinberg, who studies dance at Northwestern, said that the potential lack of space in students’ homes could hinder both their artistic development and pose challenges for the conditioning needed to safely dance. Meanwhile, for theater students, collaboration is normally the name of the game — DePaul lighting design student Kyle Cunningham defined the medium as “a gathering of people coming together to tell the story,” always a challenge at a distance. At the DePaul Theatre School, absences usually equal grade reductions — Justen Ross, an acting student, said that the policy is logical because of the vitality of in-person interaction.

“I came to DePaul initially thinking a bulk of my training will come from amazing teachers. Actually, the teachers provide the curriculum and the tools and the platform and the exercises, but within those exercises, we’re learning from each other,” Ross said. This community is, at present, a double-edged sword: students built up the trust necessary for an intimate art form, and home environments might not allow for the same vulnerability encouraged in a classroom space.

Some, like Ross, are now concerned about what they’ve paid for since experiential learning is a vital part of the conservatory experience. While Paz doesn’t take these concerns lightly, she also noted that DePaul has a particular obligation to continue educating students, if in a different form. After all, no student chooses to attend conservatory unless they’re serious about learning, and if there is a silver lining, Paz said that the shift to remote learning forces educators to strip theater to its barest bones and consider, at every turn, what they want students to learn. Only then can those objectives be translated online with the help of students, who are digital natives, as Chair of Design and Technology Victoria Deiorio pointed out.

“I teach a directing class. If I’m asking my students to ‘put a scene on its feet,’ what am I really asking them to do?” Paz said. “Then I can say, I want you to think about action, about tempo — now I’m having to break that into its smallest pieces.”

In tandem, students are also forced to think about the basics of their art form. Dance students need to learn and relearn how to clearly communicate choreography, Weinberg said, and Ross noted that professional actors and artists are in the business of uncertainty, forced to make and unmake plans at a moment’s notice.

“It’s Acting 101 that actors have to be adaptive,” Ross. “Stuff changes every second — the lights were like that 30 seconds ago and now they’re like this … This is true in our bones to know how to move around with things.”

According to acting student Kiemon Shook, the shift to remote learning allows students to focus on other pursuits that may not fit into a normal class schedule. At SAIC, Schroeder said, many older students are taking the time to focus on residency applications. And while DePaul seniors are unable to perform in their scheduled showcases, the resulting disappointment serves as an introduction to an often-unfair industry.

“We work really hard in the fourth year to make graduating students feel like they’re being launched into their careers,” Adam Crawford, a senior studying acting, said. “I have a professor who said in passing that it feels less like a launch this year and more like being dropped off a cliff. But actors are already used to being told ‘no’ and to an unreasonable level of uncertainty.” It’s lost on no one that the uncertainty within classrooms mirrors the uncertainty outside of them, as the virus continues to spread. Ross noted that creatives have a responsibility to remain present — the moment isn’t comfortable, and the resulting art can’t be, either.

“As artists, it’s our job to mirror the world,” Ross said. “And if we’re not trapped in, we can’t mirror it successfully. So I think this is if anything, good because it shows everybody that we’ve got more work to do.”

Nicole Blackwood is a freelance writer.

ct-arts@chicagotribune.com

Twitter @chitribent

by admincat | Mar 25, 2022 | Art Consultant, Evidence Based Design

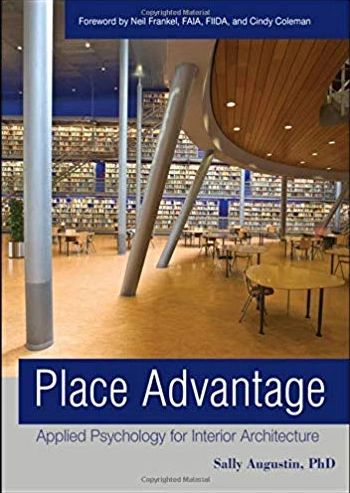

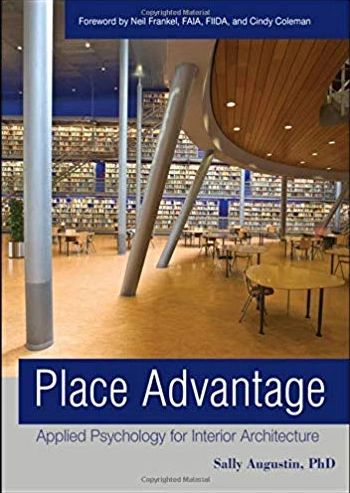

Book Recommendation – Place Advantage

Applied Psychology for Interior Architecture

Using psychology to develop spaces that enrich the human experience

Place design matters. Everyone perceives the world around them in a slightly different way, but there are fundamental laws that describe how people experience their physical environments. Place science principles can be applied in homes, schools, stores, restaurants, workplaces, healthcare facilities, and the other spaces people inhabit. This guide to person-centered place design shows architects, landscape architects, interior designers, and other interested individuals how to develop spaces that enrich human experience using concepts derived from rigorous qualitative and quantitative research. In-Place Advantage: Applied Psychology for Interior Architecture, applied environmental psychologist Sally Augustin offers design practitioners accessible environmental psychological insights into how elements of the physical environment influence human attitudes and behaviors. She introduces the general principles of place science and shows how factors such as colors, scents, textures, and the spatial composition of a room, as well as personality and cultural identity, impact the experience of a place. These principles are applied to multiple building types, including residences, workplaces, healthcare facilities, schools, and retail spaces. Building a bridge between research and design practice, Place Advantage gives people designing and using spaces the evidence-based information and psychological insight to create environments that encourage people to work effectively, learn better, get healthy, and enjoy life.

About the Author

Sally Augustin, Ph.D., is a practicing environmental psychologist as well as the Editor of Research Design Connections. She has worked with major organizations to integrate important psychological considerations into the design of places and products and has presented her work at international psychology and design-related conferences. A graduate of Wellesley College, Northwestern University (MBA), and Claremont Graduate University (Ph.D.), Augustin is also regularly invited to speak at schools and research institutions and on National Public Radio and Voice America radio programs. Learn more about using environmental psychology at Sally’s Web sites, www.placecoach.com (for residential applications) and www.researchdesignconnections.com.

Note from Health Environment Art Services

We have personally worked with Dr. Sally Augustin on a number of projects over the years. From corporate spaces to healthcare her insight, experiences and research are not only an incredibly useful tool but also essential in some spaces. Combining our companies art consultants forces with Dr. Augustin’s input is nothing less than a complete success! Our sister company Corporate Artworks has also used Dr. Augustin’s services on numerous projects. You can purchase this book here: https://www.amazon.com/Place-Advantage-Psychology-Interior-Architecture/dp/0470422122

by admincat | Mar 11, 2022 | Art Consultant, Artwork in Healthcare Settings

Book Recommendation for designing healthy workspaces

Built to Thrive: How to Build the Best Workplaces for Health, Well-Being, & Productivity

Authors: Galen Cranz Ph.D., Gretchen Gscheidle – Design Director, Gervais Tompkin AIA, LEED AP, Anthony Ravitz LEED AP, John Swartzberg MD, FACP, Kevin Kelly RA, PCAF, Sally Augustin Ph.D., Cristina Banks Ph.D., Isabelle Thibau MPH, Caitlin DeClercq Ph.D.,

Authors: Galen Cranz Ph.D., Gretchen Gscheidle – Design Director, Gervais Tompkin AIA, LEED AP, Anthony Ravitz LEED AP, John Swartzberg MD, FACP, Kevin Kelly RA, PCAF, Sally Augustin Ph.D., Cristina Banks Ph.D., Isabelle Thibau MPH, Caitlin DeClercq Ph.D.,

This book is the product of the Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workplaces’ (ICHW) inaugural Science to Practice conference in 2017 titled, “How to Build the Best Workplaces for Health and Well-Being.” In the conference, we brought together experts from different disciplines and from both research and practice to attempt to address the gaps in knowledge. Here, in this book, each author provides a perspective on the design of workplaces built for health and well-being, with the different perspectives together creating the knowledge base for successful design.

Cristina Banks, Ph.D. | Director, Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workspaces, School of Public Health and Senior Lecturer, Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley Dr. Banks holds a Doctorate in Industrial-Organizational Psychology. She and Dr. Sheldon Zedeck founded the Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workplaces in 2012. She brings 40 years of entrepreneurial, academic, and consulting experience to the Center in leading strategy and supporting the day-to-day operations of the Center. Her consulting expertise and knowledge of work and organizations help guide Center activities toward research and practice breakthroughs that will contribute significantly to the development of healthy workplaces and the promotion of worker health, well-being, and productivity.

Isabelle Thibau, MPH | Core Researcher and Leadership Team Member, Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workspaces, University of California, Berkeley Isabelle Thibaut holds a Master’s in Public Health from the University of California, Berkeley. She has served in key project development and management roles within ICHW since its inception. At ICHW, she applies a public health lens to research and consulting on workplace health and well-being issues. She joined the ICHW leadership team in 2017.

Caitlin DeClercq, Ph.D. | Assistant Director, Graduate Student Services and Programs, Center for Teaching &Learning, Columbia University. Dr. DeClercq holds a Doctorate in Architecture from the University of California, Berkeley, and a Master’s of Science in Education from the University of Rochester. Caitlin worked at ICHW as a Core Researcher in 2016 and was part of the leadership team from 2017-to 2018. Her contributions to research span multiple disciplines including education, architecture, interior design, health, and sedentary work. She is a published author with articles in the Journal of Academic Librarianship and Planning for Higher Education as well as contributed chapters in Ethnography for Designers and Experiencing Architecture in the Nineteenth Century.

Gretchen Gscheidle | Design Director, Herman MillerGretchen Gscheidle holds a Master of Science degree in Product Design and Development from Northwestern University and a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Industrial Design from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She led the corporate research function from 2010-to 2018 where Gretchen’s expertise ranged from product design and workplace applications to qualitative and quantitative research methods. She also led the team that researched and supported the new Living Office offering. She now leads design strategy for the firm.

Sally Augustin, Ph.D. | Principal, Design With Science, Inc. Sally Augustin holds a Doctorate in Environmental Psychology from Claremont Graduate School and a Master’s in Business Administration from Northwestern University. She is an internationally recognized design psychologist, specializing in person-centered design. Her knowledge and expertise regarding the interior design of commercial buildings and residences are applied all over the world. Among others, she wrote Place Advantage, which is considered a “classic” for interior designers.

Galen Cranz, Ph.D. | Professor Emerita, School of Architecture, University of California, Berkeley Dr. Cranz holds a Doctorate in Sociology from the University of Chicago and is a certified teacher of the Alexander Technique. She teaches social and cultural approaches to architecture and urban design in the College of Environmental Design. She has written and edited several books including The Body, the City, and the Buildings In Between and The Chair, both highly used references for body-conscious design. She introduced ethnography into design research for which she has been highly praised, including receiving the Career Award, the highest award given by the Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA).

John Swartzberg, MD, FACP | Clinical Professor Emeritus, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, and Chair of the Editorial Boards, UC Berkeley Wellness Letter and Health After 50 Newsletter. Dr. Swartzberg holds an MD from the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and specializes in internal medicine and infectious diseases. He teaches in the joint MD-MPH Program preparing medical students to learn about population health and prevention. He oversees the writing and publication of two highly acclaimed newsletters that have guided thousands of readers on health and wellness issues since 2001.

Kevin Kelly, RA, PCAF | Senior Architect, WorkPlace+ Project Management Office, General Services Administration, U.S. Government. Kevin Kelly holds a Master’s of Architecture from Catholic University and has worked as a Senior Architect for the General Services Administration (GSA, a government agency) in Washington, D.C. Mr. Kelly and his team developed a workplace scorecard for assessing developers of GSA properties with respect to the design quality of the building. Through Mr. Kelly’s guidance, the GSA stipulates specific features required in building contracts to ensure that quality is built into six critical areas of design: pre-design and planning, equitable workspace, health and comfort, flexibility, connectivity and mobility, reliability and sustainability, and sense of place.

Gervais Tompkin, AIA, LEED AP | Principal, Consulting Practice Area Leader, and Design Strategy Studio Director, Gensler Gervais Tompkin holds a Bachelor’s of Environmental Design from the University of Colorado at Boulder. He is a nationally recognized leader in Gensler’s Workplace Sector. Although he is based in San Francisco, his work spans the world, as he oversees global services for some of the world’s best-known tech companies. Gervais has a passion for research that has led him down a multidisciplinary path in the world of real estate strategy and design. He is driven by a desire to understand the relationship between real estate, technology, and behavior. His writing has appeared in Fast Company, IIDA Perspective, and International Design Magazine, among others.

Anthony Ravitz, LEED AP | Real Estate & Workplace Services Green Team Lead, Anthony Ravitz holds a Bachelor’s in Civil Engineering from Stanford University. He is Google’s team leader on green building as part of the Real Estate and Workplace Services team. He spearheads Google’s initiative for building healthy, eco-friendly workspaces.

Purchase the book here: https://healthyworkplaces.berkeley.edu/resources/publications/built-thrive-how-build-best-workplaces-health-well-being-productivity

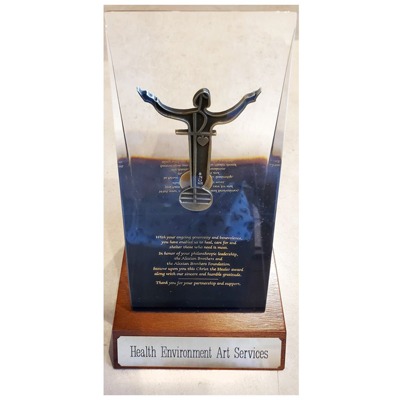

by admincat | Feb 24, 2022 | Art Consultant, Throwback Thursday

Our Journey – Throwback Thursday

We’ve come a long way with our journey for Health Environment Art Services. Starting off the New Year with remembering why it is that we do, what we do, and appreciating all of our successes large or small. This award is currently in our showroom and was given to us by Alexian Brothers Hospital located here in Illinois after we completed an amazing project with them. Awards like these from clients who are extremely happy with our services are what drive us daily to work harder.

“Never forget where you’ve been. Never lose sight of where you’re going. And never take for granted the people who travel the journey with you.” – Susan Gale

Please contact us if you have any questions.

by admincat | Feb 11, 2022 | Art Consultant, Art is medicine, Children's Health Environment

Creative Healthcare

Jane Collins, previous CEO of Great Ormond Street Hospital, London was once asked by a major donor ‘Can we afford to have art in hospitals?’ to which she simply replied ‘We can’t afford to have art in hospitals’.

When we design and build a hospital, we are building a community. Every person within a hospital is a member of that community, with a role to play. Communities need spaces where they can eat, rest, and play; where diverse populations can come together, connect and comfort each other. Hospitalization can be isolating, having central places where people gather provides a sense of not being alone, sharing challenging life experiences, belonging to a wider community, and addressing that sense of isolation. These central areas can also provide scope for the outside world to connect with those in the hospital. While the primary function is to deliver medical care, we must also attend to the emotional needs of the hospital community, providing for better mental health and greater well-being. Research tells us that the environment within which we deliver healthcare plays a vital role in health outcomes.

Art and creativity have a vital role to play within the hospital community. Art in health begins with the physical fabric of the building, but this should merely set the stage for further creative programs housed within spaces specifically designed for ongoing activities and events.

Physical artworks should engage us visually and can also be interactive so that we can engage mentally and physically with them. Art and design should be fundamental to way-finding strategies, with features integrated into theming and layering, helping us navigate unfamiliar surroundings while creating a sense of place, not just a hospital.

The art collection carefully curated by Lynne Seaar at The Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital in Brisbane is a stunning example of art enriching and personalizing the surroundings.

The best contemporary creative healthcare architecture demonstrates a clear understanding of hospital communities’ needs beyond the delivery of medical care and recognizes the need to accommodate and encourage creativity. Great hospitals no longer provide just medical facilities. Examples include spaces designed for public performance, exhibition spaces, art studios, activity centers, cinemas, even TV studios where patients can create content to be shared on bedside entertainment systems.

In children’s facilities, art and design should spark the imagination and encourage creativity and play. Keeping imagination active and vibrant is vital to their recovery. Children and young people have to be able to imagine getting better, imagine getting out of the hospital, and imagine getting back home to everyday life. Play is essential to children and young people’s cognitive, physical, social, and emotional development – teaching how to share, negotiate, resolve conflicts, and learn about themselves and others. For children and young people, play is their way of exploring and processing their experiences and surroundings and so is vitally important in a hospital setting. However, play is also very important for entire families, providing a way to connect and engage with one another in a unique, creative, and imaginative way. In designing children’s hospitals, we must provide highly visible, easily accessible spaces which facilitate all types of play and allow children and families to come together, play together – maintaining strong child-parent bonds under stressful circumstances.

A recent design brief for the new children’s hospital in Copenhagen is an exceptional example that demonstrates a clear understanding of the vital nature of play in children’s healthcare, with ‘Integrated play’ listed as one of five design principles:

“Integrated play.

Children do not stop playing simply because they fall ill. Play must therefore be an integrated part of design, life and experience. This entails not only providing play areas and playtime, but ensuring that play is fully integrated into the entire treatment process. Play can help the child accept illness and treatment, for example, if the child is allowed to treat another person or a toy animal. Play must be a common thread running through the entire stay in hospital.

We intend to take play seriously. The Academy will conduct research into – and provide training in – the link between play and recovery – with staff, families and patients.”

Another brilliant example of bespoke spaces designed to encourage play and creativity are the Starlight Express Rooms, provided to Australian children’s hospitals by Starlight Children’s Foundation. These rooms are creativity hubs that literally buzzing with excitement and fun. These spaces are designed and fully kitted out, to accommodate all manner of creative activities from arts and crafts, singing, dancing, film recording, production, screenings, gaming, etc. They are the highlight of many children and young people’s experiences of hospitalization. This is an organization that truly, deeply understands the transformative power of creativity and imagination.

Creativity should also go beyond the building and extend into outdoor spaces. Numerous studies have shown that access to the outdoors, fresh air, and sunlight are hugely important. Inspiring outdoor spaces also encourage play, creativity, and physical exercise. Strong examples of inspirational outdoor spaces can be seen at The Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital in Brisbane, Centenary Hospital for Women & Children, Canberra, and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne.

The integration of arts into both the physical environment and the creative healthcare experience has been shown to have wide-ranging positive impacts which include – reduced stress experienced by patients, families, and staff; reduced drug requirements; decreased recovery times; shortened hospital stays; improvements in clinical outcomes; enhanced quality of service provision; improvements in staff job satisfaction and well-being and generally improved healthcare experiences for everyone. With so many benefits to be gained the return on investment is high.

Jane Collins, previous CEO of Great Ormond Street Hospital, London was once asked by a major donor ‘Can we afford to have art in hospitals?’ to which she simply replied ‘We can’t afford to have art in hospitals’.

By Victoria Jones

by admincat | Feb 4, 2022 | Art & Stress Relief, Art Consultant

Unplug that Plasma Screen, Take-Two Doses of Nature

– and call me in the morning.

Can HDTV beat Mother Nature?

Do our senses really know the difference between a high-density image of nature on a television screen and the real thing? And which one is better at reducing minor stress—mountain scenery on your HD plasma TV or Doses of Nature itself?

Ask most health practitioners or psychotherapists and you will find that they intuitively agree that direct experiences with nature, such as gazing at a mountain vista or a stroll by an ocean or lakefront, have a positive effect on the body. But how do today’s technology-generated visual images of nature compare to experiences of seeing those same scenes in reality? And can we substitute this technology with individuals who may not have access to nature and obtain the same effects? As the visual images we see on our HD plasma TVs become increasingly detailed, are these images perceived in the same way we perceive that mountain vista or waves crashing on a favorite beach?

University of Washington researchers recently set out to examine whether the actual experience of nature or nature depicted on a high-density plasma screen could affect stress levels in the body in 90 college students. To do so they measured heart rate recovery from minor stress when participants were subsequently exposed to a natural scene through a window [thus eliminating sounds and smells of nature], the same natural scene on an HD plasma screen, or a blank wall. The heart rate of those individuals who looked at the natural scene through a window decreased more rapidly than in the two other situations. In fact, the HD plasma screen had no more effect than the blank wall on heart rate recovery.

Increased Blood Flow to the Brain

In May 2011, Robert Mendick, a reporter for The Telegraph, wrote an article (https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art) about an experiment conducted by Professor Semir Zeki, chair in neuroaesthetics at University College London. Zeki explained, “We wanted to see what happens in the brain when you look at beautiful paintings.” The experiment concluded when you look at art “whether it is a landscape, a still life, an abstract or a portrait – there is strong activity in that part of the brain related to pleasure.” The participants underwent brain scans while being shown a series of 30 paintings by major artists. When viewing art they considered most beautiful their blood flow increased in a certain part of the brain by as much as 10%, which is the equivalent to gazing at a loved one. Paintings by John Constable, Ingres, and Guido Reni produced the most powerful ‘pleasure’ response.

The idea that nature affects our bodies’ ability to recover from stress or illness is not a new theory. In fact, the field of hospital design has been investigating the role of nature in patient recovery for quite a few years. As early as 1984, Roger Ulrich conducted a study of patients recovering from gallbladder surgery and found that those with views of trees from their hospital windows experienced better outcomes than those looking at brick walls. Those looking at nature went home almost a day earlier, had $550 lower hospital costs, used fewer medications, had fewer minor complications, and, in general, had a more positive sense of well-being upon discharge. Ulrich’s studies and subsequent research have provided a strong argument that medical environments should be constructed to support physical recovery.

Evidence-based design is now included in most healthcare institutions because it can make measurable differences in patients’ health and hospital stays. Gardens in healthcare facilities are one of the most common design elements. They are often placed in specific locations so individuals in waiting rooms can have access to the view or near treatment areas for oncology and post-op patients. “Healing” plants—plants that have medicinal purposes—may also be included to capitalize on the notion of herbs providing certain types of pharmacological intervention.

As an art therapist, I regularly prescribe artmaking experiences that include nature and some time spent in an outdoor environment as a method of reducing stress. Clients may be sketching their impressions of a landscape or tree, painting plein air, or simply meditating on the images and sensory experiences found in nature and writing their thoughts in a journal. I wonder if people, and particularly children, are losing their direct experiences with nature and its benefits, as we come to depend on the Discovery Channel as a substitute for the outdoors. Technology is amazing, but apparently, our bodies are not fooled by it when it comes to an azure blue sky, rhythmic ocean waves, or a pine tree forest. In this time of concern for the health of our planet, it’s good to remember that by taking care to preserve nature, we are also taking better care of ourselves when it comes to stress reduction.

Reference: Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2008

When it became clear that DePaul’s Theatre School would no longer be able to hold classes in person after the novel coronavirus, Chair of Theatre Studies Coya Paz held a meeting with students. In part, she and other faculty members were looking for suggestions on how to accomplish the unprecedented: moving an inherently communal, visceral medium online. Since then, the ideas have flowed fast and loose: radio plays, an increase in playwriting courses, even a class that incorporates Dungeons & Dragons. If you asked Paz last week, she would have said that theater was a fundamentally live art. But because that answer has changed by necessity, the questions change, too.

When it became clear that DePaul’s Theatre School would no longer be able to hold classes in person after the novel coronavirus, Chair of Theatre Studies Coya Paz held a meeting with students. In part, she and other faculty members were looking for suggestions on how to accomplish the unprecedented: moving an inherently communal, visceral medium online. Since then, the ideas have flowed fast and loose: radio plays, an increase in playwriting courses, even a class that incorporates Dungeons & Dragons. If you asked Paz last week, she would have said that theater was a fundamentally live art. But because that answer has changed by necessity, the questions change, too.

Authors: Galen Cranz Ph.D., Gretchen Gscheidle – Design Director, Gervais Tompkin AIA, LEED AP, Anthony Ravitz LEED AP, John Swartzberg MD, FACP, Kevin Kelly RA, PCAF, Sally Augustin Ph.D., Cristina Banks Ph.D., Isabelle Thibau MPH, Caitlin DeClercq Ph.D.,

Authors: Galen Cranz Ph.D., Gretchen Gscheidle – Design Director, Gervais Tompkin AIA, LEED AP, Anthony Ravitz LEED AP, John Swartzberg MD, FACP, Kevin Kelly RA, PCAF, Sally Augustin Ph.D., Cristina Banks Ph.D., Isabelle Thibau MPH, Caitlin DeClercq Ph.D.,