Remote learning is necessary, but there are many challenges

When it became clear that DePaul’s Theatre School would no longer be able to hold classes in person after the novel coronavirus, Chair of Theatre Studies Coya Paz held a meeting with students. In part, she and other faculty members were looking for suggestions on how to accomplish the unprecedented: moving an inherently communal, visceral medium online. Since then, the ideas have flowed fast and loose: radio plays, an increase in playwriting courses, even a class that incorporates Dungeons & Dragons. If you asked Paz last week, she would have said that theater was a fundamentally live art. But because that answer has changed by necessity, the questions change, too.

When it became clear that DePaul’s Theatre School would no longer be able to hold classes in person after the novel coronavirus, Chair of Theatre Studies Coya Paz held a meeting with students. In part, she and other faculty members were looking for suggestions on how to accomplish the unprecedented: moving an inherently communal, visceral medium online. Since then, the ideas have flowed fast and loose: radio plays, an increase in playwriting courses, even a class that incorporates Dungeons & Dragons. If you asked Paz last week, she would have said that theater was a fundamentally live art. But because that answer has changed by necessity, the questions change, too.

“It goes back to this question of, either we think our work matters or it doesn’t. And if we think it matters, it matters now as much as it did last week,” Paz said.

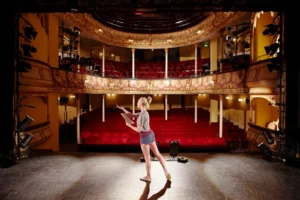

On paper, Paz’s predicament is far from unique — across the country and across Chicago, colleges and universities are shutting down in response to the spread of coronavirus, moving instruction online via platforms like Zoom. But students studying the art of any kind — visual or performing — are met with particular challenges, whether that means losing the opportunity to stage a play, use studio space and materials, or collaborate with their peers. Though the image of students dancing in front of a webcam is a funny one, the reality is, for the most part, anything but. Izzy Schroeder, a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago who works with ceramics, was left with limited options as she saw them: take home 200 pounds of clay, or wait out the storm without materials.

“I’ve talked to some of my friends at other schools and I understand that they’re losing opportunities and experiential learning as well,” Schroeder said. “But it definitely hit us hard, because we had to take the time to figure out if we wanted to do something outside of the studio, how we could do that? And I think a lot of us came to the realization that we can’t.”

SAIC student Kay Liu agreed: beyond access to technology and materials, art students often depend on in-person interactions with professors throughout projects, as well as in-person critiques. And though MFA student Anna Christine Sands is able to meet with her advisor virtually, those meetings involve sharing a screen as opposed to sharing tangible work — and nothing can substitute for a creative environment, working side-by-side with other artists.

Though the technology for online classes has been tried and tested in recent years, formatting isn’t necessarily a boon for the arts. Often, according to the University of Chicago doctoral candidate Ailsa Lipscombe, who studies Music History and Theory, online platforms include functions that normally help to mimic a classroom environment — automatically putting other students on mute when one is speaking, for instance — but actually detract from ensemble students’ typical learning, which relies on simultaneous sound. While UChicago’s music department is working to mitigate challenges, collecting free software licensing and renting instruments, Director of Undergraduate Studies Jennifer Iverson noted that the real challenge is adaptability, keeping education accessible while moving students forward on both academic and creative paths.

“We can’t expect that online courses are a replacement or a seamless substitute for what we would’ve had in person,” Iverson said. “But nothing about our lives in this moment is comparable to the normal.”

And some students have broader concerns. Samantha Weinberg, who studies dance at Northwestern, said that the potential lack of space in students’ homes could hinder both their artistic development and pose challenges for the conditioning needed to safely dance. Meanwhile, for theater students, collaboration is normally the name of the game — DePaul lighting design student Kyle Cunningham defined the medium as “a gathering of people coming together to tell the story,” always a challenge at a distance. At the DePaul Theatre School, absences usually equal grade reductions — Justen Ross, an acting student, said that the policy is logical because of the vitality of in-person interaction.

“I came to DePaul initially thinking a bulk of my training will come from amazing teachers. Actually, the teachers provide the curriculum and the tools and the platform and the exercises, but within those exercises, we’re learning from each other,” Ross said. This community is, at present, a double-edged sword: students built up the trust necessary for an intimate art form, and home environments might not allow for the same vulnerability encouraged in a classroom space.

Some, like Ross, are now concerned about what they’ve paid for since experiential learning is a vital part of the conservatory experience. While Paz doesn’t take these concerns lightly, she also noted that DePaul has a particular obligation to continue educating students, if in a different form. After all, no student chooses to attend conservatory unless they’re serious about learning, and if there is a silver lining, Paz said that the shift to remote learning forces educators to strip theater to its barest bones and consider, at every turn, what they want students to learn. Only then can those objectives be translated online with the help of students, who are digital natives, as Chair of Design and Technology Victoria Deiorio pointed out.

“I teach a directing class. If I’m asking my students to ‘put a scene on its feet,’ what am I really asking them to do?” Paz said. “Then I can say, I want you to think about action, about tempo — now I’m having to break that into its smallest pieces.”

In tandem, students are also forced to think about the basics of their art form. Dance students need to learn and relearn how to clearly communicate choreography, Weinberg said, and Ross noted that professional actors and artists are in the business of uncertainty, forced to make and unmake plans at a moment’s notice.

“It’s Acting 101 that actors have to be adaptive,” Ross. “Stuff changes every second — the lights were like that 30 seconds ago and now they’re like this … This is true in our bones to know how to move around with things.”

According to acting student Kiemon Shook, the shift to remote learning allows students to focus on other pursuits that may not fit into a normal class schedule. At SAIC, Schroeder said, many older students are taking the time to focus on residency applications. And while DePaul seniors are unable to perform in their scheduled showcases, the resulting disappointment serves as an introduction to an often-unfair industry.

“We work really hard in the fourth year to make graduating students feel like they’re being launched into their careers,” Adam Crawford, a senior studying acting, said. “I have a professor who said in passing that it feels less like a launch this year and more like being dropped off a cliff. But actors are already used to being told ‘no’ and to an unreasonable level of uncertainty.” It’s lost on no one that the uncertainty within classrooms mirrors the uncertainty outside of them, as the virus continues to spread. Ross noted that creatives have a responsibility to remain present — the moment isn’t comfortable, and the resulting art can’t be, either.

“As artists, it’s our job to mirror the world,” Ross said. “And if we’re not trapped in, we can’t mirror it successfully. So I think this is if anything, good because it shows everybody that we’ve got more work to do.”

Nicole Blackwood is a freelance writer.

Twitter @chitribent